I ended last year’s metabology finale with a hint that I might be doing something different in the new year. It’s the new year isn’t it? 2026 stretches into the haze in front of me. I am ready to plot my course into the unknown.

Forgive me for a very long essay. This article is going out on the first Monday of the year, but for reasons I explain at the end, the project outlined in it will take a while to go public.

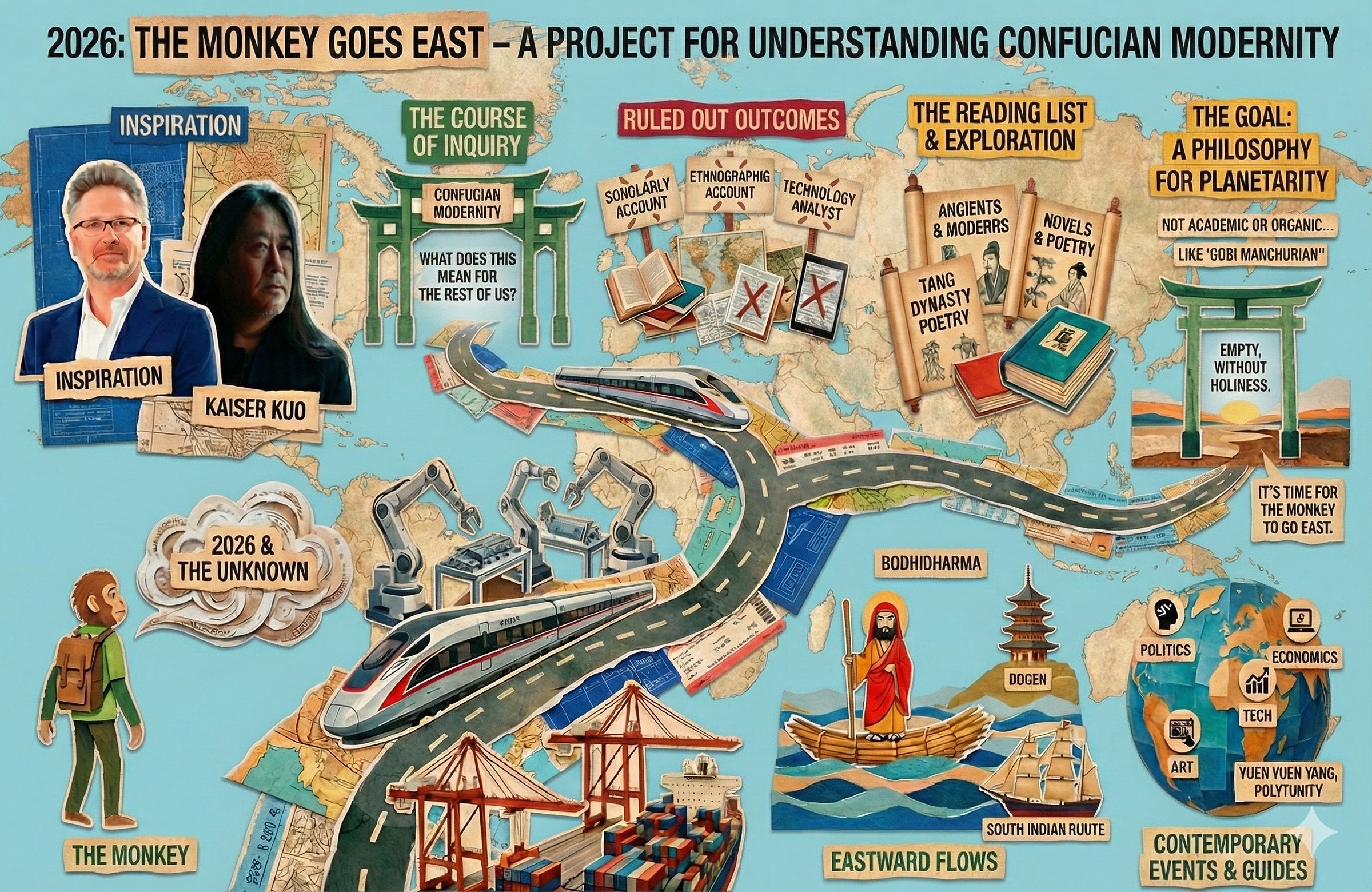

TLDR: 👇🏾 check out the infographic 👇🏾

The Musician and the Professor

I’ll start with two names: Kaiser Kuo and Adam Tooze.

Chances are, you haven’t heard of either, but of the two, Adam is by far the better known. Even if you haven’t heard his name, you might have heard the concept he’s made famous: “Polycrisis.” Tooze is an acclaimed historian at Columbia, a writer of thick books, who pivoted to being perpetually online and has become the resident liberal sage on Twitter.

One of the few academics who has become a celebrity on Twitter.

Kaiser Kuo, is best known for his Sinica podcast, though he has also had avatars as a musician - having fronted a band called ‘Tang Dynasty’- and a writer. I had heard a couple of Sinica episodes but Kuo’s name stuck in my head after I read a remarkable essay written by him: The Great Reckoning: What the West Should Learn From China. Very early on in that essay, Kuo quotes Tooze saying:

“China isn’t just an analytical problem,” he said. It is “the master key to understanding modernity.” Tooze called China “the biggest laboratory of organized modernizations there has ever been or ever will be at this level [of] organization.”

Both Kuo and Tooze are obsessed with the possibility that the future of modernity is in China, not the West - a disorienting thought. Confucian modernity, centered on China, but with distinct East Asian variants is an emerging reality, one whose idioms and reflexes aren’t widely understood. Now pair Tooze’s and Kuo’s sober assessments with this take from Afra Wang’s recent essay in the Ideas Newsletter:

His China did not arrive through the frameworks I inherited from college professors, journalists, or scholars. It came through other channels: viral videos of synchronized drone shows, TikTok montages of Shenzhen’s skyline, tech bloggers’ analysis of DeepSeek’s efficiency, Cantonese rap circulating through global youth culture, hardware tutorials filmed in Hangzhou studios by Chinese tech influencers. For Aadil, China is more than a geopolitical puzzle. China is modernity itself.

Note the last line!

Besides Afra’s (or rather, Aadil’s) pronouncements, there are many signs there’s a distinctly Confucian modernity that can’t be reduced to a history of Capitalism or post-war growth. Take the crudest measure of success: GDP growth figures of Japan, Singapore, South Korea,Taiwan and China since 1945. Pretty remarkable isn’t it? Seen from a Western lens, these societies are quite different - some are officially “Communist,” some are American protectorates and one is a city state. Nevertheless, they have something in common. After all, if you took a picture of Europe since 1945, you would also see city states, communist societies and American protectorates, but you wouldn’t want to deny their collective European-ness would you?

How might we understand Confucian modernity on its own terms?

What does Confucian modernity mean for the rest of us, those who don’t belong to either engine of history, West or East?

I want to understand the metabology underlying this remarkable rise, the combination of political, economic and material order that makes Confucian Asia the (likely) most important part of the globe in the 21st century. And just to be clear: this future isn’t all rosy - the social control and hierarchical order we see across today’s China, and especially its metastasized versions in Xinjiang and Tibet, are as disturbing as the alienated dystopias we inherit from the West.

Some of us as CONFUCED

I want to spend some time exploring this question, but not as a Whig history of Confucian modernity starting with Kongzi and ending with Xi Jingping. Therefore, I can rule out certain outcomes right away:

A scholarly account of China, whether modern or ancient. I am not going to be a historian, a philologist, an intellectual historian or anything that scholars in the “Letters” part of the “School of Letters and Sciences” tend to do.

An ethnographic account of China, based on extensive personal travel and time spent with communities there. Not going to happen this year or any year in the near future. No Breakneck in the Dan Wang style either.

A technology analyst who looks at Chinese advances in AI and renewables or someone who reports on China’s emerging leadership in Climate Action.

A new cold war analysis of China versus the US and their relative strengths. Is China winning? Will the US back China into a corner? Nope, not me.

These are important functions, but they are all being done by people way more knowledgeable than I am. I would rather write murder mysteries with a Chinese detective as the main protagonist than an academic text. More seriously, I believe:

There’s such a thing as the Confucian Metabology, with historical continuity and a modern avatar.

Modern Confucian metabology is distinct from other metabologies but mutually comprehensible to the others. It’s not exotic at all; in fact, it’s familiar. This is most certainly not the ‘Clash of Civilizations,’ but it’s not convergence to the liberal ‘End of History’ either. That’s what’s fascinating about our current moment.

Discerning the (idealized) architecture of Confucian metabology is as much the task of the Cognitive Scientist as it is that of a historian.

That idealized architecture is never going to be found in some pure form in actual Confucian societies, but it’s the norm that the rest of us can learn from the most.

The rise of Confucian Asia - first Japan, then South Korea, Taiwan and China (including Hong Kong) and also Singapore - is a bigger story than the first Cold War or the second Cold War. Between them, they have metabolized democracy, capitalism and Leninist communism. In combination, they present the biggest challenge to Western ideas, ideals and institutions in five hundred years.

Confucian modernity isn’t exotic or unintelligible - no more so than France is to Americans - but it’s a distinct form of modern existence.

We are used to explaining this emerging Confucian alternative in western conceptual terms. Japan’s rise from the Meiji restoration onward is always clubbed with its defeat to the US, the dropping of the nuclear bomb and then subsumed under the US empire. In this recounting, Korea is part of the American empire too. And then China’s rise is seen as part of the communist revolution and its aftermath. That’s carving up Confucian modernity along Euro-American Cold War lines, which was fine as long as we were living inside the Liberal International Order, but surely it’s a bad schema for describing Confucian modernity itself! I want to explore Confucian modernity on its own terms, where the period from the Meiji restoration onwards has its own logic.

What is that logic? What are its drivers? What are its principles?

Those are my questions. Also, on the fun side of this exploration, I want to understand why embodied AI (robotics, industrial automation etc) has been so much bigger in Confucian Asia than in the West with geopolitical consequences, but I am less interested in the politics around Embodied AI than in understanding if there’s a strain of Confucian Intelligence that can be contrasted with the Cartesian Intelligence that dominates western thinking and engineering around AI. Way back when I was a kid, my brother and I were major fans of this Japanese TV show called The Giant Robot, and it never struck me until now that the humanoid imagination arising out of Japan and now led by China might have deep cultural roots. Think about it as the Embodied Mind with Chinese Characteristics.

We - and by “we” I mean “all of humanity” - face unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. So far, we have assumed, despite loud protests in some quarters, that the way out of our Polyconflicts will be grasped on terms set by WEIRD people. That time has come to an end. Our planetary future will not only be dictated by WEIRDs (Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democracies, it will be influenced by the CONFUCED (Confucian Eastern Dominions) too.

I don’t expect the ascent of the CONFUCED to end for any reason besides demographic ones - TFRs ~ 1.0 is a bigger problem than tariff, sanction or war.

Chindia

An aside on a matter of personal concern

Twenty years ago, it was common to combine China and India into a single emerging conglomeration called “Chindia.” We were the poster children of neoliberal development - growing at a fast clip, destinations for outsourced manufacturing (China) and outsourced services (India).

Chindia feels quaint, if not laughable. China is no longer emerging. It has emerged. As infrastructure goes, it is a ‘developed’ country. India, meanwhile, is stuck in a deadly combination of crony capitalism and authoritarian politics. As I write this piece, Delhi’s AQI is 279. Beijing’s is 26. A lot of India is unbreathable and unlivable in comparison to most places East of it.

Steve Jobs famously said that “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” You could say the same about Development. It has to work. I am not a fan of high energy and material use models of growth, or a single party state for that matter, but most of the Indian elite has bought into both. They want the trains to run on time, and they want the masses to do what they are told. And self serving as they are, that elite hasn’t delivered the outcomes they themselves desire.

Take a cab from Bangalore’s airport to the city center, and you will pass hoardings of real estate developments that promise a Singapore (or Shanghai) life in your private bubble. What happens outside the gates of that bubble isn’t their concern.

The fact is, even our elites are dispensable. Our most important export - software - is getting eaten alive by AI. India, as a credible alternative to Western modernity, is a pipe dream and the culture that has replaced it is unattractive to everyone besides those who have drunk the kool-aid. Absolutely no one thinks we are a hedge against China, and any romance about the Ramakrishna-Tagore-Gandhi-Ramana alternative to muscular modernity is long gone. Instead, we have been consumed by political Hinduism, aka Hindutva, which is repulsive. Let’s not forget about caste either, which has to be annihilated. A lot of our problems are due to (mostly upper caste Hindu male) Indian elites preferring to lord it over their small pond while ignoring the ocean that’s knocking on our doors. No wonder the rupee is in free fall (breached 90/dollar while I was writing this essay).

We have self-serving elites, who would rather protect their social and economic position than to let the rising tide lift all boats: both during the license raj and post-liberalization.

Let me illustrate this claim with six points derived from this interview with Ha-Joon Chang:

We started about the same as our Confucian counterparts, but they made better investments and better choices.

We have a ‘trader’ mentality that would rather make a quick buck via finance than invest in manufacturing.

We don’t invest in the future or think in the long term: our investments in human capital development and R & D are shockingly small.

The few advantages we have are going to be swallowed by AI, which is a bigger threat to us than to most others. The same is true of climate change, but that’s a story for another day.

Our elite fights tooth and nail to keep its relative position, even if it means weakening us relative to the rest of the world.

We need to spread the wealth if we are to stand a chance.

1. We started about the same

South Korea was a very poor country until the early 60s. In 1961, India’s per capita income was $88 and South Korea’s was $94. Essentially, the same level of development.

South Korea also protected its fledgling industries:

In 1976, Hyundai produced 10,000 cars. That year, Ford produced 1.9 million cars. General Motors was approaching 4.8 million cars. Now if South Korea had free trade in cars back then, Hyundai would have disappeared overnight… This is what is called infant industry protection. They developed automobile, electronics, shipbuilding, all these industries through similar measures.

India was only superficially similar:

In India, until the 1980s, protection was used to preserve existing producers rather than giving them the space to accumulate production capabilities and go out in the bigger world to fight…That kind of protectionism doesn’t work. Protection only works when you use it to develop your own infant industries, so that they can export to the global market.

2. We want to make a quick buck

The business elites are either in the financial sector or, even if they are in the industrial sector, they still have very strong links with financial capital which doesn’t like industrialisation because, for them, the most important thing is the rate of return….Your elites do not want to wait for 10 or 15 years and sacrifice short-term financial returns to build productive capabilities.

3. We don’t invest in the future

You need to invest in worker skills, infrastructure, and research and development (R&D). I looked up the latest data on R&D in India, and as a proportion of GDP, it is barely 0.6 per cent, compared to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) average of 3 per cent, and South Korea’s 5.2 per cent.

which is why we don’t build the future:

Secondly, India has been touted as a success story of services-based development. But this strategy, when compared to what China has achieved in the last 25 years, pales into insignificance….

4. AI is going to eat our lunch

I am not one of those people who think that AI will completely change the world in the next five years…India will be one of the biggest casualties of AI. It needs to get out of there, it needs to industrialise.

5. We don’t take care of our own

Consider East Asian countries where, despite all kinds of bad things happening, military dictatorship, one party rule, repression of worker rights and everything, they sustained their growth trajectory because they shared that growth with the poorer people. All of them had land reforms and, even though they had very small welfare states, they had a lot of protection for the weak guys.

6. But we absolutely need to

So, this extensive concentration of wealth at the top in India is a huge problem…. Even if you belong to the elite, it is in your long-term self-interest to share some of your wealth with the poorer segments of the society. Because otherwise, they will destroy the system.

I can’t stress how precarious a moment this is for India. We got lucky for the first 75 years after independence. We had exceptional leadership for the first two decades, and even after Nehru’s death, the Cold War gave us maneuvering room and then, when the Soviet Union collapsed, we had our niche in Pax Americana.

None of those conditions hold anymore.

The liberal international order has collapsed and the new multipolar world is a dangerous place. One in which we have no friends or well-wishers because we are bereft of kindness ourselves. Indian social media personalities gloating over Palestinian children getting killed en masse is all you need to know about the state of our public discourse. AI is automating the few good jobs we created, though as coolies, and if that weren’t enough, climate change is going to devastate large parts of the sub-continent.

We are heading towards a civilization crisis - if not collapse - and the only thing we are capable of doing is building temples upon the ruins of mosques and calling it justice for centuries of humiliation. When a bully claims to be the victim, you know that:

truth is the real victim

you invite bigger bullies to show who is the real boss

When you don’t matter, others can choose to be patronizingly generous, or bully the fuck out of you. In today’s world, the latter is our lot. Cue the immense uptick in anti-Indian racism in the West and tariffs picked out of a hat.

Ever since the anti-colonial independence struggle, Indians have thought that they offer an alternative modernity. Dream on. Meanwhile Confucian Asia, with China at its center - is showing its fleshed out and increasingly attractive alternative. We may not like it or want to emulate it, but Indians need to introspect and change, and studying the idealized metabolite of CONFUCED societies is a necessary component of that introspection.

I am not naive in thinking China is a friend in the making; that’s unlikely to be true in my lifetime. But we can learn from our adversaries can’t we? Isn’t that what the Japanese did when Commodore Perry came knocking on their door?

I will never want to give up our diversity, our resistance to uniformity, our love of argument and metaphysical speculation, the genuine religiosity and the deep acceptance of the non-human world. But we need to open the windows of our house to the winds of the world.

The “Great Reckoning,” as Kuo calls it, demands intellectual honesty. The West must acknowledge China’s successes without dismissing them or clinging to outdated narratives that expect China to fail or conform to Western norms. The same goes for India - there’s no need to surrender our civilizational strengths, but we should learn from China’s achievements and strengthen our institutions through clear-eyed self-examination.

We have to understand both the good and the bad parts. I really like these lines from an amazing conversation between Jordan Schneider and Dan Wang:

you have four decades of astonishing growth from China, in which the country was growing at a rate of 8 or 9%. That created tremendous wealth, alleviated poverty, and made a lot of Chinese right now feel really good about what the country was able to accomplish. This is where I really want to grapple with both the good aspects as well as the bad aspects of China. Yes, it’s absolutely the case that the wealth creation here was astonishing. That has been much more impressive than what any other developing country was able to achieve — India, Indonesia, Brazil have not had the economic takeoff that China enjoyed that brought so many people out of misery and poverty.

At the same time, we have more novel forms of political repression that humanity has never seen before. Both of these trends are real, and they both have to be acknowledged.

And

Xi comes off as someone who is a little too eager for groveling respect from the rest of the world, which is exactly why he’ll never get it.

Modi and Trump are cut from the same cloth, but Xi has the greatest leeway of the three to impose his whims. We will do well to understand the maximalist version of authoritarianism.

Charting a Course

How can we learn from the CONFUCED? What does Planetarity look like if it emerges from CONFUCED societies? WEIRD culture beams into our homes and screens 24/7, but we have very little exposure to the Middle Kingdom. Here’s my plan:

Read some ancients: Kongzi, Mengzi, Laozi, Zhuangzi, Xunzi, Hanfeizi, Mozi etc.

Read some moderns: Hui Wang, Wang Huning, Dan Wang…

Read some old novels: Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, Dream of the Red Chamber…

Read some Indian things that went East: Buddhist literature in particular, and Chan Buddhist literature to be even more precise.

Read some India → China things that went even further East: Dogen comes to mind, but also more contemporary figures such as Nishida Kitaro.

That’s an assortment of things that have struck my fancy. And a drop in the Confucian ocean. And these are the big names.

At some point I will tire of the superstars and start exploring lesser known figures. There’s also the flow of contemporary events - a steady drip of ongoing news about what’s going on in China today, whether politics, economics, tech, business or art, with many contemporary guides: I have already mentioned Kuo and Tooze, but let me also acknowledge Yuen Yuen Ang and her work on Polytunity.

Then what?

Not this, Not that

I don’t know what will come out of this exercise.

Not this

The outcome shouldn’t insult a Chinese citizen or scholar. I am not interested in producing a hagiography in the “Making China Great Again” genre. I am not interested in showing how India used to be great and how we did China a favor by exporting Buddhism across the Himalayas.

Yes, but

On the plus side, the writing should feel true and insightful to a person born and brought up in China - even if it’s not true and insightful about China, like how Gobi Manchurian isn’t a Chinese dish at all, but can be a delicious snack when prepared well in an Indian restaurant.

Not that

It should be a work of philosophy, but not one that can be produced in academia, or its opposite - by an ‘organic intellectual’ either. It shouldn’t be scholarly or popular. Neither factual nor fictional. And if that’s not enough: all of it should be written under the condition of Planetarity; I am trying to understand Confucian Metabology after all.

And…

I want to grok China as China, without being reductive. I’m OK mistaking the Dragon for a Dinosaur, but I don’t want to be a blind monk that grasps the tail of the Dragon and thinks it’s a snake.

Most importantly, as a complete beginner to this exercise in metabolic and cultural understanding, I want to write in the simplest and most easily understandable language. I want to ELI5 myself, and then share that understanding with others. This essay is far from ELI5, so forgive me this one time and hold me to that standard from now on.

Wall Staring

There’s a semi-mythical South Indian route through these paradoxes; it’s sometimes said that Bodhidharma, the monk who founded Chan Buddhism (Chan = Zen, both being derivatives of the Sanskrit Dhyan) was a Pallava prince from Kanchipuram, not too far from my ancestral home. South India has a long history of contact with China; among other things, the wealth that funded Raja Raja Chola’s spectacular Brihadeeswara Temple came from trade with China via Srivijaya. There’s a Ramayana connection too - Anthony Yu points out in his translation of “Journey to the West“ that there are many similarities between the Monkey character in Wu Cheng’en’s Epic and Hanuman in Valmiki’s Ramayana.

Correlation? Causation?

I don’t know.

That don’t know mind is also in operation in the first case of the Blue Cliff Record:

Emperor Wu of Liang asked the great master Bodhidharma, “What is the highest meaning of the holy truths?” Bodhidharma said, “Empty, without holiness.” The Emperor said, “Who is facing me?” Bodhidharma replied, “I don’t know.” The Emperor did not understand. After this Bodhidharma crossed the Yangtse River and came to the kingdom of Wei.

Did Bodhidharma actually say so to Emperor Wu? Did he actually meditate for nine years facing the Shaolin Temple Wall after cutting off his eyelids? His trip East might have ended in tragedy: in one account, Bodhidharma was killed by the banks of the Luo river in the mass executions at Heyin. Is that true?

I don’t know.

But the koan gives us an opening to lay a mythical road from India to China and back. They say about Chan that it is “a separate transmission outside the scriptures.” I don’t know if a separate transmission is possible under conditions of Planetarity. Or desirable. I hope so! But failure is always an option - my efforts can join a long line.

Buddhism - both its conceptual categories and its historical trajectory - gives us a rope to hold on to as we travel to the East and back.

In Parting

Towards the beginning of this essay, I mentioned that I want to understand Confucian Modernity in China with Japan and Korea as sister exemplars; but that project requires a continuous thread from Kongzi to Xi Jinping. Nation states love to invent historical continuity, but is it real?

I don’t know.

I am biased towards a positive answer, but that doesn’t mean I will take it for granted. Even if the continuity is a fact, one has to do a lot of work to show that today’s investments in Embodied AI are of a piece with the Laozi and the Blue Cliff Record. I am not sure it’s possible to show metabolic continuity across the centuries, and even if it’s possible in principle, whether I am the right person to explore that question.

I will be happy with the Gobi Manchurian version of China’s intellectual history.

Wu Cheng-En’s “The Monkey Goes West” is a fictionalized, mythical account of Xuanzang’s long pilgrimage to India. Is it an accurate account of Xuanzang’s travels? Nope. Does it capture the essence of Xuanzang’s pilgrimage and why it was considered a landmark event? Absolutely.

It’s time for the Monkey to go East.

There’s continuity with last year’s intent. If you remember, I started by reading Machiavelli’s The Prince in a planetary frame and over the course of the year meandered into metabolics and metabology. There’s no way I could have predicted the ending from the beginning. In retrospect, I wasn’t reading the Prince for reading the Prince, but to open up new planetary pathways. Perhaps this year will be the same. I will start with reading Chinese texts in translation, give them a planetary reading and see whether I can monkey Confucian metabology as I go.

It’s going to take a while for me to make these Sinological musings public. In the meantime, I will continue with planetary and metabological analyses, both of my own as well as reviews of contemporary texts.

Mostly according to Frederick Starr the India-central Asia-Europe intellectual area developed independently from the Chinese intellectual area, at least in terms of science and scholarship. Is the rise of global prosperity and the study and translation of Classical Chinese texts leading to a reintegration of separate historic scholarly thought? Is this likely to trigger a burst of synergistic advance in various knowledge domains? If generative AI develops wider and different learning source data might it also push similar synergy and acceleration?

Looking forward to it.