The Great Unsettling

Introduction

I have written a few hundred essays over the last five years, with a year and a half in the middle being devoted to a single text, the Mahabharata. I might start the Jayary again this fall, prompted by a seminar I am organizing this semester.

The Mahabharata is unique in that it starts with a post-apocalyptic scenario: a great war has ended, killing everyone except for seven survivors, a death toll of millions. There’s recognition that the old order has ended, that it was unsustainable and that its end came despite the societies of that time being led by people considered "good" by the standards of the time.

Perhaps we too are such a society, led by regimes with some legitimacy but collectively heading towards a transition that we can't plan for or avoid. What form will that transition take? What will be washed away? Those are the questions that I keep returning to, provoking a meandering journey through the forty two gates of knowledge.

To put it simply, there's an itch I want to scratch, but each time I scratch one spot, it starts itching in another. I don't want the itch to go away, but I would like to know the source of the irritation.

Mission accomplished last week: I found the source. I bet you're itching to learn what I found. Here's a clue:

Elrond: "This peril belongs to all Middle-Earth. They must decide now how to end it."

Elrond: "The time of the Elves is over — my people are leaving these shores. Who will you look to when we've gone? The Dwarves?

Gandalf: "It is in Men that we must place our hope."

One of my (many) favorite lines in the Lord of the Rings, describing a world that's about to pass. If you haven't read the books, here's the premise: the dark lord has emerged from his hideout and is gathering his forces. If he wins, game over: everyone's dead or his slave. If the good guys manage to defeat him, the dharma of the elves is fulfilled and they have to fade away.

Either way, one yuga is over and another is about to begin.

Fast forward a few thousand (or is it million?) years and we are at a crossroads once again. Just as the elves had to fade away after Sauron's defeat, we might have to fade away too: except that we are the good guys and the bad guys, so if our bad guys win, we are all done for and if our good guys win, we will have to make away for something else.

What I don't know is whether the future will transform the world we have created over the last seventy five years after the end of the second world war, or the world we have created as a settled species over the last ten thousand years. I tend towards the latter, hence the sensationalist slogan:

The age of men is ending.

Whether it's a rejection of the last 75 years or of the last 7500, we are in for a great unsettling.

Photographer: Patrick Hendry | Source: Unsplash

Apocalypse?

Let's get rid of the Sauron scenario first: I am not thinking apocalyptically. Major violence is almost certain, but I am skeptical about futures lacking in humanity altogether.

Let's say all of Eurasia outside Siberia becomes uninhabitable because of climate change and Russia refuses to change its immigration policy in response, leading to pitched battles over migration and settlement. How many people do you think will die? A few hundred million? A billion? It would still be a smaller loss, relative to population, than what happened in China over the 13th century after the Mongol invasions, when a population of 120 million collapsed to 60 million over six decades.

Even if we are left with a human population of 4 billion in 2100 - undoubtedly the outcome of the greatest disasters in the history of humanity - it will still leave enough humans that the species is not threatened. In other words, whatever happens, there are going to be people left on earth. Lots of people.

The real question is: who will they be and how will they live?

Settler Humanity

For most of human history, we were a mobile species. It's only with settled agriculture sometime in the last ten thousand odd years that we became "rooted." It's fair to say that what we call history is nothing but the chronicles of settler humanity; even when they were conquered by nomadic tribes - the Mongol invasions for example - it was in order to loot or skim off the wealth created by settler humanity.

In fact, the concept of wealth is a settler concept; a mobile species has no reason to accumulate.

Settler humanity has won to such a large extent that for most people including me, the only ways of life are rural or urban, i.e., agricultural settler humanity and industrial/post-industrial settler humanity. Non-settler humanities - often captured by the blanket term "indigenous peoples" - are barely 5% of the human population and every single one of them lives at the mercy of settlers.

I will not recall the long and torturous expansion of settler humanity across the globe, the waxing and waning of agrarian and industrial civilizations. We can say that all of that came to a head in the second world war, at the end of which were two "final settlements" that vied for support across the world: communist society and liberal democracy.

In the history we have written so far, one of them won and the other lost. I am thinking that's that not the final verdict for they were both heading towards the wrong finish line.

When the Soviet Union fell, scholars such as Fukuyama thought we had arrived at a secular, this-worldly end of all times. In that moment of triumph, liberal capitalist democracy represented the end of history, a city on the hill that approximates the universal ideals of settler humanity. Which is to say that after an agonizing journey filled with disease and violence and predatory social relations that extracted wealth from the majority of toiling humans, we had created the institutional framework that made most people happy most of the time.

I think Fukuyama was right, in that all that toil and struggle produced a brief period under US hegemony when it seemed like a global settler human will become the universal ideal. Unfortunately, that ride into the sunset turned out to be a short stroll to the edge of the abyss. Instead of a final settlement, we are the beginning of a great unsettling, where every idea, ideal and institution of ours will be questioned, rejected, transformed or destroyed.

To give just one example: do you think we can continue to live in a world of sovereign nation states when hundreds of millions of people are desperate to migrate with their lands running out of water and their oceans frosting their fields with salt?

I have a hard time believing in that settled future.

There are many many other unsettlings waiting to happen and I hope to chronicle some of them. While there are many objects that catch my fancy, ultimately, my essays are a dairy of the great unsettling. And when I turn to the Mahabharata, I read another era's retelling of their great unsettling and the painful recreation of a world worth living. That's the source of my itch.

There's still uncertainty over what will be unsettled: will it be the post-world war liberal order or will it be all of human history? I tend towards the latter, which is what I mean by the claim "the age of men is ending," but even a rejection of the last seventy five years will be a great unsettling.

Caveat: Dramatic claims need extraordinary evidence. I am not arrogant enough to think one essay is enough evidence in the court of the cosmos. I am arrogant enough to think that an essay can make that claim vivid enough that further evidence will make it plausible and ninety three volumes later, lay the foundation of a cult in my name.

Meanwhile, as an educator, the great unsettling prompts some questions about learning to live through the shift -

how to imagine life as we enter that phase?

what skills will help us navigate its uncertainties?

and most importantly for me professionally - how will the world of knowledge be unsettled?

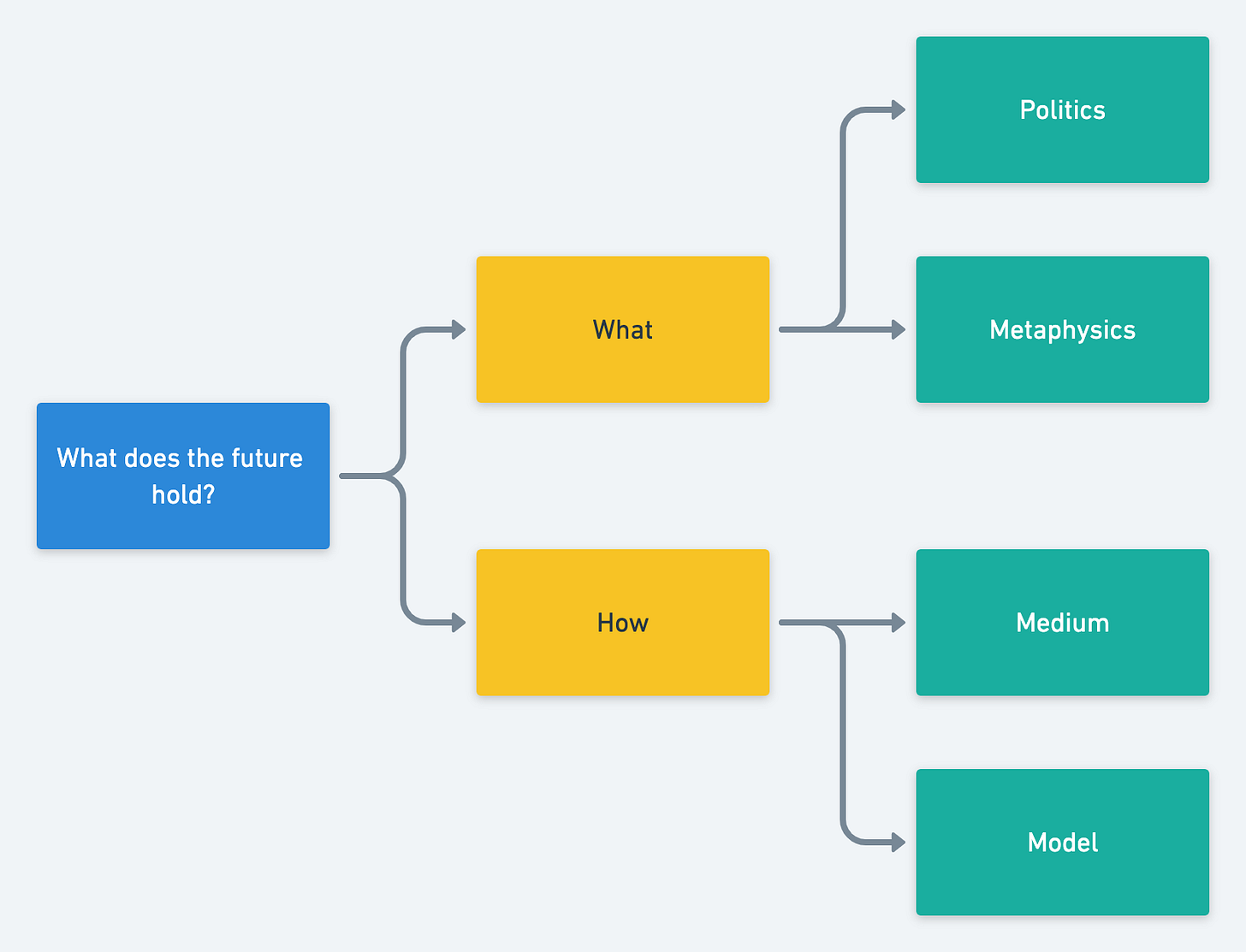

I will leave you with a diagram that captures my answer to that question. More about it next week.