Making Sense of Sensemaking

I am traveling for the next couple of weeks and not sure how often I will be writing while I am on the road. Some philosophical thoughts to end this week.

There are things that start as mysteries and stay that way until the mystery is resolved and there are things that feel obvious and slowly take on a mysterious hue. Example of the first: God. Starting with their existence, we wonder who or what is God and whether we can know them. Or the fundamental laws of the universe: we don’t know what they are until we do. Example of the second: consciousness. Everyone knows what it is to be conscious and it takes enormous effort to question its immediacy, whether that’s done via philosophical probing or through artistic exploration.

The social world is usually in the second camp except when enormous changes are afoot. One of the questions that I keep coming back to in my reading of Tagore, Gandhi and Lenin is: how did they make sense of the ongoing transformation of their societies? Bourgeois imperialism was a strange beast: it promised equality and prosperity. It rolled out tantalizing new technologies. & it exerted control and extracted resources at a speed and scale no one had experienced before & it killed and starved people en masse.

How did GTL make sense of it all?

Behind that question is the common observation that we take the world for granted: people, places, things etc all appear to us as they always have and we don’t have to think or wonder why they are the way they are.

It’s only when the world manifests strange things do you wonder: what is it I am seeing?

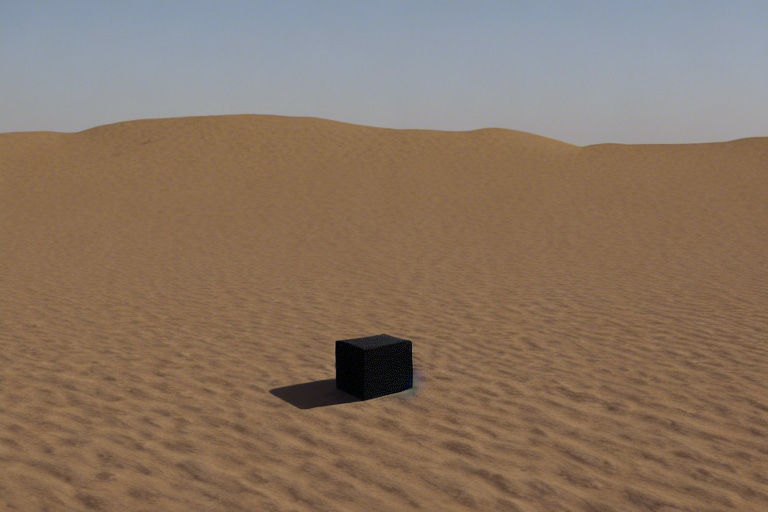

Say you are wandering in a desert and you come across a black cube about six feet high. I am imagining a sentinel of the kind that Arthur C. Clarke wrote about in 2001, a black perfection that came out of the void. It presents a smooth face to you but the rest of it is covered in sand. Here's a question: do you think it's a cube hidden underneath the sand or a portal to some unknown world? What do you think it is?

One of the first things you are going to do (if you are courageous - otherwise the first thing you're going to do is to back away real quick and put as much distance between yourself and that cube) is to start clearing the sand away. Suppose you do that and more and more flat black smoothness comes your way. At some point you are going to make a leap of faith and say: "behold, here's a cube."

Which is to say, the absent shape is being fleshed out by your intending consciousness. While the absence is empty, it's not an unformed emptiness. Not all possibilities seem equally plausible to you as you flesh out the shape as the sand is stripped away. Where do those constrained possibilities come from?

Regularities

Consider another kind of absence. You are hiking along a forested mountain path and you see smoke pouring out of the trees near the summit. What do you infer? Chances are you think it's a forest fire and if you're smart you're going to be running away from it pronto. That fire is as much an intended absence as the black cube in the desert. Except that it's got an even more definite form.

Where did the form of that intended absent fire come from?

Answer: Regularities

Regularities are the glue that connect the manifold of experiences into an identity, but they extend well beyond experience.

Regularities help us make sense of the world.

More generally, we take for granted that the world makes sense. Some of that sense making is of the conscious kind: you open your eyes and a scene presents itself in front of you. There's a little coffee cup a foot to your right; it's easy to take your right hand off the keyboard, grab the cup, smell the aroma of fresh ground beans and taste the hot liquid as it flows on to your tongue and descends down your throat.

Easy peasy. It's like that every single day you're alive. Every once in a while this ease of being fails, like when you run into a transparent window. It's a bigger problem for birds than for us but we are susceptible to the illusion too. Glass houses aside, illusions are scarce. We mostly see what we hear, touch what we see, tell people about what we have touched and sleep assured that all's well with the world. While you might enjoy the Matrix so much that you have seen it seven times, there's no convincing you that the world in which you wake up every morning is an illusion. In fact, it's the very definition of what's not an illusion.

Then there’s sense making of a non-conscious kind, a lot of which can be attributed to trust: trust in institutions, trust in people, trust in technologies and most generally, trust in the world. I trust that the room in which I wake up is the room in which I slept the previous night - no Cartesian devil has switched out one room for another. I don’t need to experience all aspects of the world - trust that the world is ordered and regular is all I need. Which is to say: as long as I am not plagued by Cartesian doubt and devils don’t haunt my dreams, I am ok letting the world be what it is.

The world doesn’t need to reveal itself to me, it just needs to be.

In fact, we trust our sense-making so much that we are willing to accept gaps between appearance and reality - the sun only appears to revolve around the earth; in reality it's the other way around. If there was only appearance, then the question of a revolution in sense-making wouldn't even arise. Since the world makes sense, it will reveal the truth behind the appearances if you look close enough. And so we refine our instruments, build bigger telescopes and microscopes and look ever more closely.

The difference between appearance and reality is because we implicitly trust we are already embedded in reality.

At some point, the gaze turns inward. As the world makes more and more sense, it's natural to ask what is it that constitutes sense-making. Probing one step further, two questions arise:

1. How do we make sense of the world?

2. Why does it make sense at all?

Conceptual progress depends on close integration of why questions with how answers but the situation is quite lopsided. Understanding how we see or smell the world is hard, but we have made enormous progress - after all, it's the basis for common sense as well as all of science. You see water on your pavement and you conclude that it must have rained overnight. Or you're upset at your neighbor for not spraying water everywhere. Or you see a photograph in a cloud chamber and conclude that it must be the particle you've been looking for several years. We express the how of sense-making in the language of data, evidence, inference, neural pathways and information processing.

But why does it make sense at all? Why is it not a confusion? If you set aside religious or philosophical ideas and concentrate on theories that are grounded in empirical research (or try to make sense of that empirical research), we have only two serious contenders:

The Kantian idea that the world makes sense because our mind imposes structure upon the world.

The Darwinian idea that the world makes sense because those who couldn't make sense of the world are inside the bellies of those who couldn't.

Add a dollop of modern genetic explanation and the two why theories can be combined into one: the world makes sense because we have evolved to be genetically hardwired to interpret the world as being the way we normally sense it as being. Unlike the crisply articulated how theories - for example, we see the visual world by inverting the image that forms on the retina - the why theories are complex, intricate networks of arguments that are hard to test.

I have a problem with both accounts - or the joint account for that matter, but this is not the place to reveal my complaints.