The key insight for me from these three chapters was the sign of the interregnum that Machiavelli unknowingly chronicles. He says about ecclesiastical principalities:

Only they have states and do not defend them, and subjects whom they do not trouble to govern

i.e., the power of spiritual and moral authority was so strong that they didn't have to do anything else to rule; no welfare state to run or enemies to destroy. As a result, they weren't taken seriously as military powers either. But Pope Alexander (father of Cesar Borgia BTW, so not a celibate!) destroyed that equilibrium by:

Then Alexander VI came to the papal throne; more than any previous pope, he showed how much a pope could achieve through money and military means.

The flip side of it being: the moral order was no longer enough - both the opportunity to wield power and money were too attractive and the hold of the spiritual was weakening. This shift from spiritual to temporal power marks a crucial turning point that Machiavelli captures, perhaps without fully realizing its historical significance.

As the Church began competing in the realm of military might and material wealth, it inadvertently weakened the very foundation of its authority - its moral and spiritual supremacy, but that might have been weakening anyway. This transformation provides important context for understanding Machiavelli's detailed analysis in the following chapters, where he examines how principalities should measure their strength, the unique nature of ecclesiastical power, and the critical role of military forces. Let's examine each of these chapters in turn.

Commentary on Chapters 10-12

Chapter 10: In What Ways the Strengths of All Principalities Should Be Measured

There is another consideration that must be borne in mind when examining the qualities of principalities: namely, whether a ruler has sufficient territory and power to defend himself, when this is necessary, or whether he will always need some help from others.

To clarify this matter, let me say that I consider that a ruler is capable of defending his state if he can put together an army that is good enough to fight a battle against any power that attacks it (either because he has many soldiers ofhis own or because he has sufficient money) But a ruler who cannot confront any enemy on the field of battle, and is obliged to take refuge within the walls of his city, and keep guard over them, will always need to be helped by others.

Comment: What does territory and power mean? The economy is a much greater source of power today than it was in M's time. If you set aside a North Korea, it's hard to imagine a military power that isn't backed by serious economic heft.

Therefore, a ruler who possesses a strong city and does not make himself hated is safe from attack; and anyone who should attack him is eventually forced to beat an ignominious retreat.

Comment: Besides wealth and arms, legitimate Rule makes it less likely your populace will revolt or capitulate during a siege.

Chapter 11: Ecclesiastical Principalities

since they are controlled by a higher power, which the human mind cannot comprehend, I shall refrain from discussing them; since they are raised up and maintained by God, only a presumptuous and rash man would examine them. Nevertheless, someone might ask me how it has happened that the temporal power of the Church has become so great, although before Alexander’s pontificate the leading Italian powersc (and not only those called ‘powers’, but every baron and lord, however unimportant) held this temporal power in little account, whereas now a king of France stands in awe of it

Comment: note that the Papacy's temporal power was a new thing, not a given. It's the temporal power of the Church that invites tussle with the State and leads to secularization. The problem for the Church is that its purely moral power is also being eroded elsewhere, not by the State but by the increasing complexity of social life.

Chapter 12: How Many Kinds of Soldiers There Are, and Mercenary Troops

Since it is impossible to have good laws ifgood arms are lacking,b and if there are good arms there must also be good laws,c I shall leave laws aside and concentrate on arms.

Comment: Speak softly or speak loudly, but always carry a strong stick

The rest of this chapter is Machiavelli's deep distrust of mercenary armies. Like when he says:

Mercenaries and auxiliaries are useless and dangerous; and anyone who relies upon mercenaries to defend his territories will never have a stable or secure rule.

I have the counter question: how did anyone manage to create standing armies? They are expensive, and being permanently armed, they are a potential danger to the Prince.

Contemporary Reflections

Just as Machiavelli unknowingly chronicled the transition from medieval to modern authority, we may be witnessing a similar epochal shift. The post-WWII liberal order, built on nation-states, market capitalism, and democratic institutions, shows signs of transformation or decay. Like the Church in Machiavelli's time, which could no longer rule through spiritual authority alone, our current institutions seem increasingly unable to govern through their traditional means.

Consider three parallel transformations:

From Moral to Material Authority: Just as the Church had to resort to "money and military means" under Alexander VI, today's liberal democracies increasingly rely on surveillance, economic coercion, and hard power rather than moral leadership. The US's declining soft power and increasing use of sanctions, or China's technological authoritarianism, exemplify this shift.

From National to Planetary Politics: The nation-state system, like medieval principalities, faces challenges it wasn't designed to handle. Climate change, artificial intelligence, and global pandemics transcend borders. Yet our response, like medieval princes scrambling for territory, often retreats to nationalism rather than addressing these planetary-scale issues.

From Institutional to Networked Power: Traditional hierarchical institutions (governments, corporations, universities) are being disrupted by networked forms of organization. Everything from iPhones to Airplanes are manufactured by ‘ecosystems’ that cut across national boundaries.

Yet this transition, like Machiavelli's time, is marked by violence and uncertainty. The rise of authoritarianism, the weaponization of information, and increasing geopolitical tensions suggest we're in what Antonio Gramsci described as a time when "the old is dying and the new cannot be born."

The key question becomes: will this interregnum lead to new forms of democratic organization capable of addressing planetary challenges, or will it result in more sophisticated forms of authoritarianism?

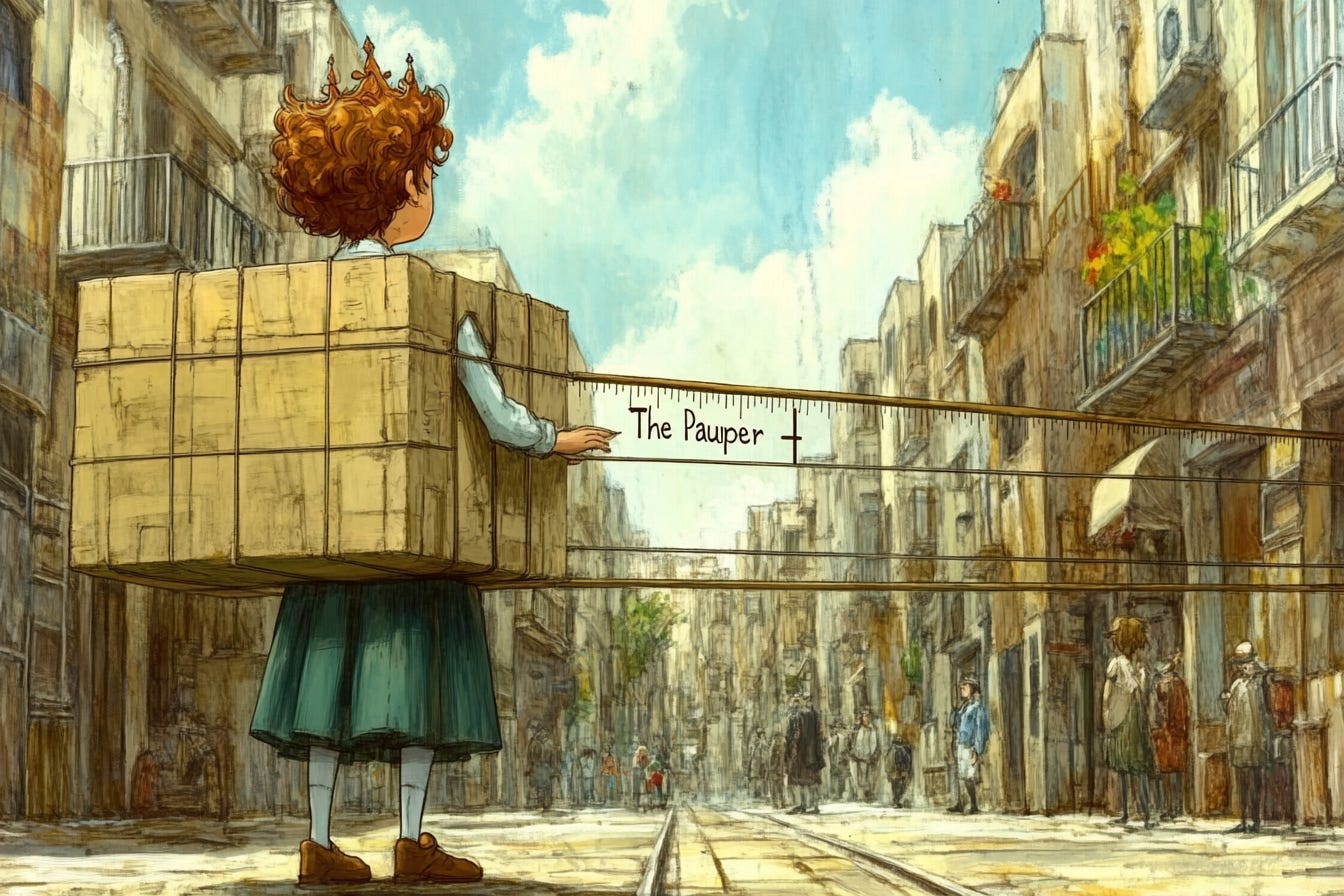

The Pauper’s Perspective

If we are indeed in an interregnum between the post-WWII liberal order and whatever comes next, the pauper's position is both precarious and potentially powerful. Machiavelli's insights about power remain crucial: those who rely solely on fortune rather than systematic organization will fail, and those who remember freedom are the hardest to subjugate. The challenge for the pauper is to build new forms of planetary-scale organization without falling into the traps of either naive utopianism or cynical realpolitik.

The first step is recognizing that planetary politics doesn't mean global homogenization. Just as Machiavelli advised princes to either destroy republican cities or live among them, today's movements must choose between trying to capture existing institutions or building alternative ones from below. The most successful approaches might combine both: using existing democratic channels while simultaneously creating new forms of organization that transcend national boundaries.

Consider how mutual aid networks during COVID-19 demonstrated the possibility of coordinated action without central control. These networks weren't just local - they shared information and resources globally while maintaining local autonomy. Similarly, climate activists are creating transnational networks that combine scientific expertise with local knowledge, showing how planetary-scale challenges can be addressed through distributed but coordinated action.

The pauper's advantage lies in flexibility and distributed organization. While states and corporations must maintain rigid hierarchies, citizen networks can adapt and evolve. When one approach fails, others can emerge. This is not just about resistance but about creating new forms of power that are inherently more democratic because they're built from the ground up.

M would say: spontaneous protests and viral social media campaigns won't be enough. The pauper must learn to think and act strategically, building lasting institutions that can weather political storms. This means developing what Machiavelli called virtù - the capacity to act effectively in changing circumstances - but at a collective rather than individual level.

In the emerging planetary order, the pauper's path lies not in rejecting computational power but in redirecting it toward democratic ends. This might mean creating open-source alternatives to corporate platforms, developing citizen science initiatives for environmental monitoring, or building decentralized systems for resource sharing. The goal is not to oppose the state (why? the State has legitimacy that citizens sorely need as they organize) but to supplement centralized control through the creation of resilient, democratic alternatives.

The interregnum offers an opportunity to shape what comes next, but only if we can organize effectively at both local and planetary scales. The pauper's task is to turn this moment of uncertainty into one of democratic renewal, building power from below while remaining clear-eyed about the challenges ahead.