This post is the first short post in a series of frequent short posts on the emerging Polyconflict.

I thought I would be writing about the intertwined fates of carbon and silicon over the next few weeks, but as usual, the real world has other plans. I keep saying that the polycrisis is giving way to polyconflict; that climate change is primarily understood in polycrisis terms (if at all that) but we should prepare for it to metastasize into a polyconflict. This week's news has, sadly, strengthened my hypothesis.

I was boarding a flight to Doha on my way to Bangalore when we heard that Israel had attacked Iran. My flight was rerouted to avoid flying over Iraq and Iran; I was half expecting to see missile trails out of the window. Doha airport was in chaos. Many flights, including all flights to North India and Pakistan were canceled; fortunately, I was going much further south, so I landed in Bangalore on time.

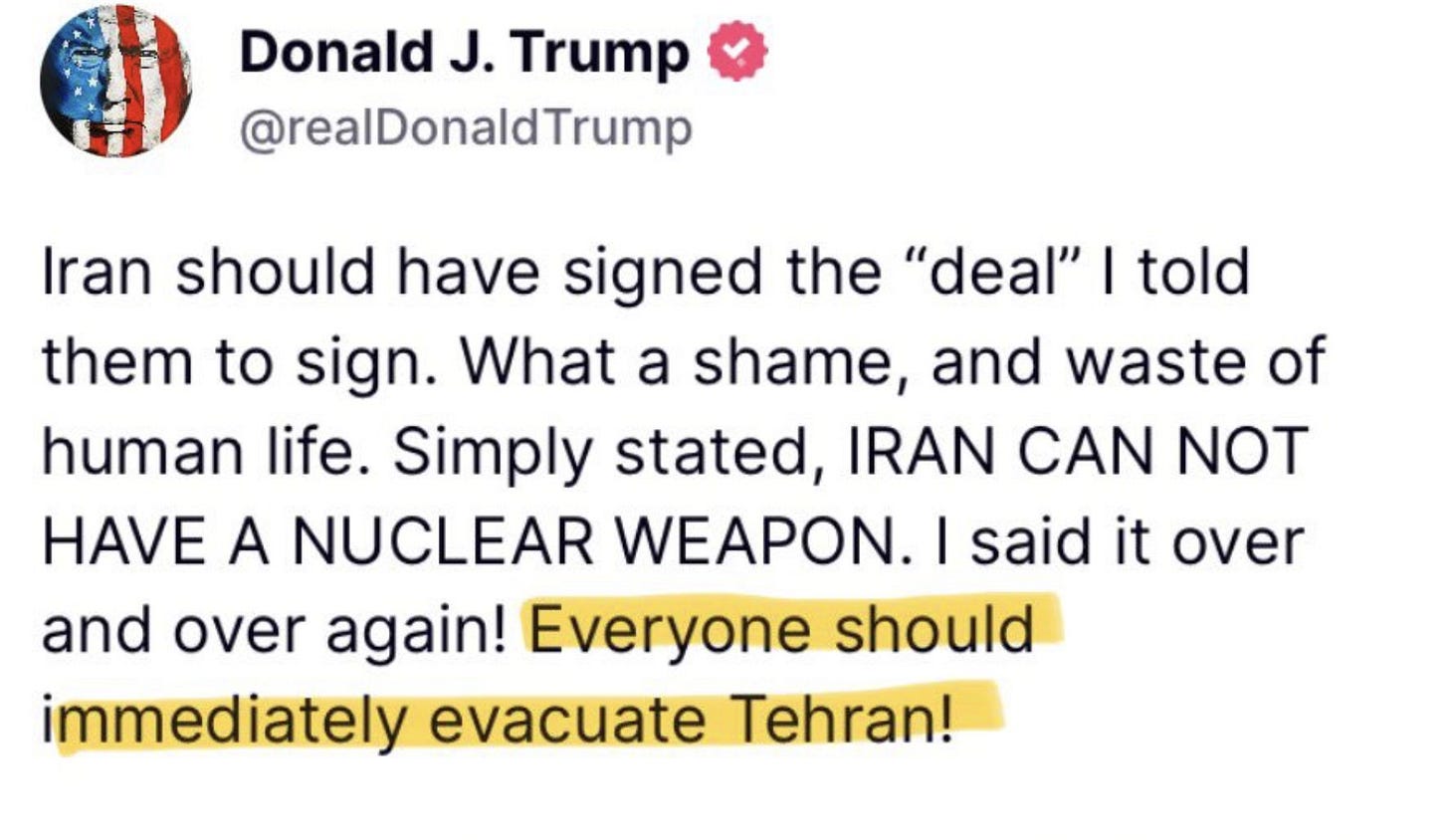

Israel and Iran have gone after each other this week in unfortunate, if predictable, ways. I don’t have any love lost for the Islamic Republic of Iran; its revolutionary potential is reactionary potential as far as I am concerned. But in this war Iran is neither the aggressor nor is it mistaken in wanting to defend itself. Israel is going from strength to strength, from its settler colonial roots to an apartheid state to genocide to the fifth horseman of the apocalypse. In response, the Donald is telling everyone in Tehran to leave the city.

Well played.

I don’t know how this conflict is going to play out, but it’s clear that every nation will try to acquire nuclear weapons as quickly as possible. It’s the rational response to unprovoked attacks by the hegemon. Here’s one piece of evidence in that direction:

Recent polling in 2025 shows that public support in South Korea for acquiring indigenous nuclear weapons has reached an all-time high. According to the Asan Institute’s 2025 poll, 76.2% of South Koreans support developing their own nuclear weapons, with 66.3% also supporting the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula. This is the highest level of support recorded since such surveys began in 2010, reflecting a significant increase over previous years.

Of course, there will be a corresponding nuclear tragedy of the commons, since rapid proliferation of nuclear weapons will make the world more unstable for everyone. The climate crisis as polycrisis is a familiar beast - we know it makes everything worse, but it's possible to lament its worsening while sipping cocktails at the World Economic Forum or Aspen. But climate catastrophe married to a newly resurrected possibility of nuclear war married to rising authoritarianism the world over: that's a polyconflict demanding unprecedented urgency.

We have to be Machiavellian about this polyconflict: not in the negative sense of scheming for advantage, but by being clear-eyed about the dangers that beset us and a robust understanding of power in a planetary age. I am putting the carbon-silicon thread on hold for a few more weeks as I grapple with these challenges.

The Israeli attack on Iran isn't just another episode in a long-running regional conflict - it represents the perfect storm of polyconflict dynamics. Here we see nuclear capabilities, religious fundamentalism, settler colonialism, and authoritarian tendencies converging with climate vulnerabilities and resource competition. The Middle East is already one of the regions most threatened by rising temperatures and water scarcity. Adding potential nuclear escalation to this volatile mix demonstrates how polyconflict differs fundamentally from polycrisis - there's no "management" solution here, only strategic navigation through increasingly dangerous waters.

What's particularly striking is how this situation exemplifies the criminalization of international relations I've discussed in previous essays. Israel's actions, like those of many powerful states today, increasingly resemble those of sophisticated criminal networks - operating outside international law while maintaining a veneer of legitimacy, exploiting governance gaps, and creating facts on the ground through raw power rather than legal process.

This isn't about moral equivalence but about understanding the actual dynamics of power in our new era.

The challenge for those of us trying to think through planetary governance isn't just about preventing escalation or managing conflict - it's about developing new frameworks for collective survival when the old rules-based order has given way to naked power politics.