This is a rambling meditation on the interregnum; if you remember, a few months ago (see link in the inset below), I started writing about the time of monsters and how the rules-based international order is dying. But that's just one aspect of the headlong fall of liberalism and liberal values.

As I experience that fall, I also find certain types of public discourse more puzzling than I would have a year ago - moves that make sense only against the background of liberal hegemony have started becoming questionable.

Questionable not in a bad/good kind of way, but in a ‘it’s time has come and gone’ kind of way.

Where I introduce monsterology 👇🏾

There was a time when I used to be a keyboard warrior, but COVID ended those ambitions; I just didn't have the appetite for telling people they were wrong and I was right. Since then, I have more or less stopped writing about contemporary politics, especially that of countries of which I'm not a citizen (with the genocide of Palestinians being an exception).

The recent murder of Charlie Kirk woke me up.

I must admit that I didn't know much about him. I'd heard his name, and I think I'd heard about Turning Point USA, but I had no idea that this was an influential man. That tells you less about Charlie Kirk and more about me and how I grasp U.S. politics. If you name a senator, chances are I would have heard of that person. I know who Tommy Tuberville is, but I often draw a blank when it comes to cultural figures that orbit around politics, sometimes with great influence. The Billy Grahams of the world - religious figures with secular influence - are the only exception. Maybe it's an age thing for Steve Bannon shows up on my TL while Charlie Kirk didn't. But mostly, it's because I don't pay attention to the informal cultural politics surrounding formal institutional politics. I didn't grow up in the US and I don't have friends who are sending me hot-takes on YouTube. In contrast I have heard about the Indian counterparts of Charlie Kirk and Tommy Tuberville and many more such creatures.

Anyways, the man was murdered and that is a bad thing, as much gun violence as it is political violence. I see it as murder, not an assassination; it doesn't matter whether that person was murdered for being a political enemy or shot while being mugged. Murder is murder, and that's wrong, and I hope the perpetrator is brought to justice.

I don't want to talk about the murder as political violence for several reasons - one being that Charlie Kirk is already being mythologized for welcoming opportunities to sit across the table from his opponents and having a good old fashioned debate. Others dispute the mythology, saying his method of arguing with his opponents was one of bad faith, of bullshit, one that did not care about the truth at all, that he used the debating podium as a way of scoring political points that can be spun later on social media.

Both might be true, but I have a more fundamental question:

Is one of the best things about democracy that you can argue with your opponents, have fierce debates, and then go back home and not kill each other?

Not killing each other is a good thing, but is the apocalypse being held at the breach by speech? Like if we stopped talking, the guns will come out blazing? Is talking to people who aren’t like you a guarantor of peace?

I am not convinced TBH.

Debates play a much bigger role in American politics and maybe in some other Western countries (I don't know much about the public spectacles that inform their politics) than they do in Indian politics. Speech, especially oratory, is central to Indian politics, but Indian politicians don't conduct campaigns that end in debates.

But that's not my point either.

Indian politicians do all kinds of things that American politicians don't. We are not here to perform comparative analyses of political speech. Let's get back to debate. Debates are important in American politics. Not too long ago, Joe Biden was forced to end his campaign for the presidency because of how he performed in a debate. But here too, maybe the debate is not the important thing. It's not that he lost the debate on substantive grounds or even that his opponent was able to twist the rules of debate to win in the eyes of public opinion.

Actually, the truth was quite different, which is that Biden came across as old and senile and therefore incapable of running for president. It had nothing to do with the substance of the debate at all and everything to do with the mental state of Joe Biden.

Which brings me to a bigger issue: is the ability to talk it over with your opponents somehow the best thing about a democracy? That if we ended civil debate, we would be on the road to autocracy before you know it? That of all the ways in which politics reconciles cooperation and competition, debate and other forms of argumentative speech are the most important?

I am skeptical.

Compare debate as a non-explosive form of disagreement with other ways of being with people with whom we disagree. Let's take eating a communal meal. Suppose we replaced debates with people of opposing views sitting at a table and having a meal. Would that lead to a better political culture? I don't know. But all of us have experience of food diplomacy. My family doesn't agree with me on politics, but I sit at a table and eat with them all the time. And the solidarity created by food keeps me going back to that table. If I have to make a choice between debating and eating, I stop debating. Food is a greater binding element than the ability to disagree.

These visceral aspects of democratic life: eating at the same table, occupying the same spaces, going to the same schools - these factors also have the quality of reducing violence, perhaps more so than the ability to sit across the table and debating your opponents.

Hat-tip to A.O. Hirschman, who pointed out that ‘let’s make a deal’ was the original defense of capitalism, deals being much preferred to duels.

Debate is only a small part of the story of language in social life - take one look around you and notice how speech has become a semi-mystical wellspring of democracy. It isn't surprising, because modern technology allows one to 'speak' to millions while we can only eat at a table with ten, maybe, a hundred people.

I am skeptical of speech in the public sphere; it runs to demagogy even when it claims not to.

In the United States, the veneration of freedom of speech is an interesting thing. Don’t get me wrong: it's a good thing, it's good to have freedom of speech. I would rather be in a place where you could speak freely. But even then, is speech at the foundation of freedom? Is freedom flowing out of the nature of language or is it coming from somewhere else? We have a tendency to think that language like institutions - laws, constitutions, contracts etc - are the building blocks of collective human life. Of course everyone admits they are idealizations, but note that:

1. We idealize by reducing messy reality to a rule bound linguistic model and argue that the idealizations capture an essential truth.

2. There's a sense in which ideologies are nothing but clusters of propositions that hang together.

3. At its extreme, all of social life becomes a language game.

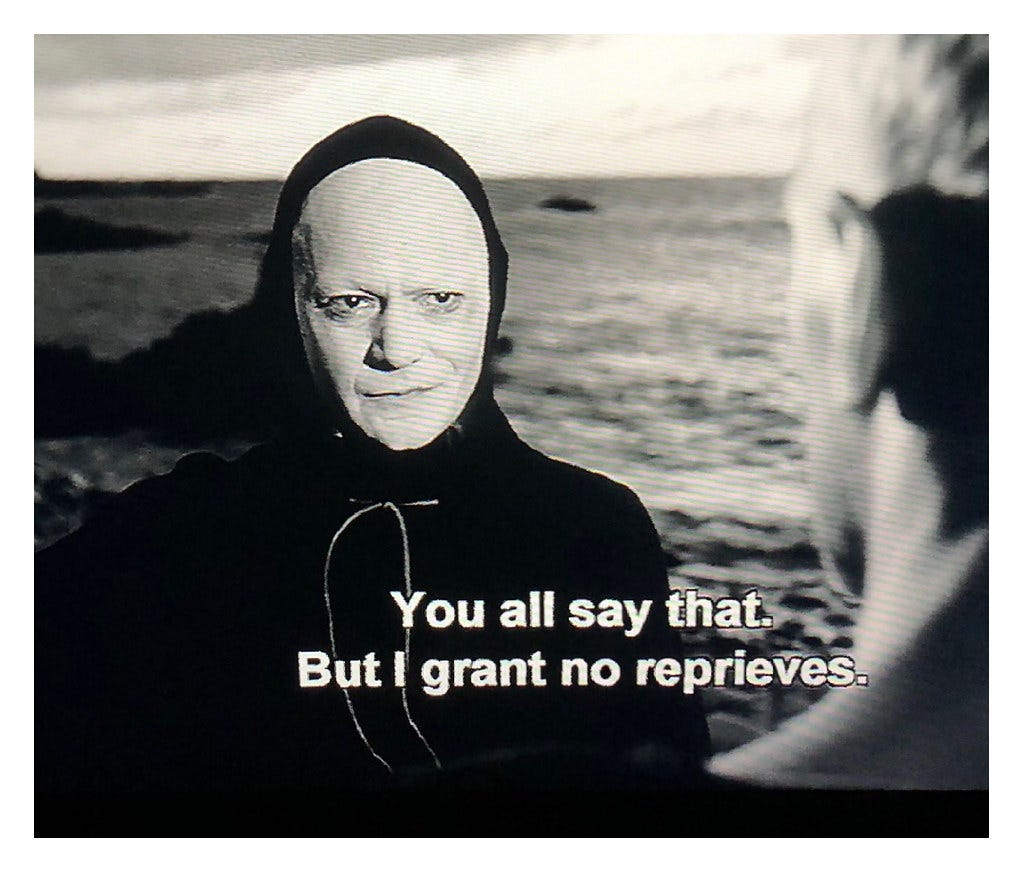

Debates and other language-game negotiations are reasonable idealizations when the world has already been brought to a stage where the conflicting parties accept the terms of the debate. We might think that paints a nice, liberal picture, but what happens when the debate’s terms are enforced by men with swords? Instead of treating language as an autonomous sphere, recognize that it’s embedded within many other conflicts (and cooperations). I am reminded of a famous debate between Buddhists, Daoists, Christians and Muslims organized in Mongke Khan’s court (MK was Genghis’ grandson):

This first face-to-face exchange on religious doctrines between East and West took place a few days later, on May 30, 1254, the eve of Pentecost. On this day, Rubruck represented Christianity, engaging in debate with Nestorians, Saracens, and Taoists within the church. Möngke appointed three arbitrators—a Christian, a Saracen, and a Taoist—and prohibited any claim that another’s view was inconsistent with God, banning insults and noisy disturbances.

Nevertheless, the debate did not end well for some of its participants. Daoists found themselves facing the sharp end of the sword while Tibetan Lamas found favor at the court. I doubt if the loss of favor was for purely scholarly reasons - sometimes you’re playing a game for fun, sometimes you’re playing to win a prize and sometimes you’re playing a game with death! You better know which one you’re playing. Otherwise, you’re like Neo trapped in the Matrix, enjoying the pretense of freedom while robots rule the world.

It doesn’t surprise me one bit that across the world, tricksters are celebrated for breaking the rules of the game - from Oedipus to Birbal, they recognize that the pen sits athwart the sword and you need to keep an eye on both.

TLDR; As long as the liberal hegemony holds, we can conduct our social affairs as if they are language games, that we can trade arguments and commodities, as if an equilibrium could be reached through the rules of the game - sometimes with a market in the middle, sometimes with a voter in the middle.

But if that liberal hegemony falls apart, it's not clear that these games can be played uninterrupted or when they aren’t interrupted, whether the outcomes have meaning. As infrastructure replaces ideology and metabolics replaces economics, should we also expect speech to be replaced by....?

I don’t know the answer to that question, but we need to channel some of that trickster energy to get there.

As you can see, I started with Charlie Kirk, but then meandered my way into puzzles about language in the social sphere. That's the power of the interregnum, when sometimes an event is just an event, and sometimes an event is an EVENT.

Moral of the story: the Interregnum needs Trickster energy