Last essay of the year.

TLDR;

Ideology tells us what kind of world we think we are building. It provides the map of intentions, the moral compass, and the political manifesto. Metabology reveals the world we are actually building. It is found in the contracts signed, the dashboards monitored, the sensors installed, the favors exchanged, the algorithms deployed, and the energy consumed.

To understand modern power —and more importantly, to change it— we must descend from the high altitude of ideologies and laws into the tangle of metabologies on the ground. In this last essay of the year, I argue that civilization is metabolism before it is politics, economy, or culture.

Metabology is a guide to the flows of energy, matter, and information that constitute the material basis of social life, and an invitation to rewrite the protocols that govern them.

The Ideological Cascade

Consider socialism. As an ideology, it posits that the means of production should be socially owned. If you are a state socialist, you believe the state should hold that ownership. From this ideological stance, a specific policy goal might emerge: providing abundant, cheap electricity to everyone. This is consistent with the belief that access to energy is a social good. In the realm of ideology, this belief must translate into policy.

The Plan: A Planning Commission incorporates this into a “Five-Year Plan,” promising, for example, one kilowatt of free electricity to every family.

The Bureaucracy: The Ministry of Power allocates budgets to different regions based on reported needs.

The Distribution: Regional ministries receive funds and invite tenders from power suppliers to install solar capacity.

The Outcome: Contracts are signed, panels are imported and wired, and - in theory - electricity flows into the grid.

This entire chain, from the high-level principle to the final kilowatt, operates within the logic of the ideological model. Get it? No? Let me say it again:

The Ideological Cascade Illustrated

Let’s say you think the means of production should be owned by the state. In that case, one of the things the state might want to do is provide abundant, cheap electricity to everyone. Ideologically, that’s consistent with the state owning the means of production and with the belief that access to abundant energy is a social good. All of that is still in the realm of ideology.

But then someone has to take that ideological belief and turn it into actual electricity flowing into people’s homes. So maybe - as used to happen in actually existing socialist states - there’s a planning commission that says: in this five-year plan, we are going to provide one kilowatt of free electricity to every family in the country. The party secretariat and the planning commission agree that this is how the principle of socialized energy will translate into a policy outcome: one kilowatt per family.

But how are you going to get to that one kilowatt?

They might say: “We have the Ministry of Power, and the Ministry of Power has to allocate its budget to different regions in such a way that we build solar farms that actually produce that energy.” Different regions then apply to the Ministry of Power, saying: “This is what we need. This is our average electricity production, here’s how we’re falling short of our one-kilowatt goal, and please give us this much money.”

The Ministry of Power distributes money to all the local or state-level or regional power authorities. Those local authorities then have to distribute funds to people who will actually install the capacity and “get the wires going,” so to speak. Each local ministry invites tenders from power suppliers, solar power suppliers in this case. They say: “Bid for our contracts and tell us how much you’ll charge for installing this much solar capacity in this region, in this year.”

Once the contracts are awarded, the solar companies hire people, import solar panels from China, and eventually you start seeing solar panels going up. They’re wired into the grid, and assuming every family has a connection, they start getting electricity - one kilowatt of installed capacity per family.

The Metabolic Reality

Now, strip away the ministries and the high-level abstractions. Look simply at the coordination occurring on the ground. You have solar companies, local agencies, financial flows, and material constraints like sunlight availability, grid stability, and roof space.

How exactly are information, finance, and materials combined to execute this? What rules or heuristics govern those local interactions?

This is metabology. It starts with embodied interactions - people shaking hands over a contract or a solar installer climbing on a roof - and builds abstractions on top of those. Currently, we often view these ground-level mechanics merely as the “last mile” of ideological policy. However, the reality on the ground is often messy and distinct from the theory. For instance, a contractor might bribe a bureaucrat to secure a bid. That corruption is certainly not “socializing the means of production,” yet it is part of how the system actually functions.

Metabology asks us to treat those messy mechanics not as noise or “implementation details,” but as the main story. Instead of starting from grand principles and working downward, metabology starts from the ground up and asks: what are the protocols by which decisions actually get made, resources actually move, and systems actually run?

Think of metabology as the operating system of a society’s material life. Where ideology tells you why energy ought to be shared and who ought to own the means of production, metabology tells you how, step by step, that belief turns into electrons moving through wires, steel being poured, or food showing up in a neighborhood market. It is concerned with rules-of-thumb, bidding procedures, software systems, bribes and favors, informal hierarchies, physical bottlenecks, and data flows. All of these together form a set of protocols - formal and informal - that govern the flow of energy, information, money, and matter.

In an idealized socialist story, the Planning Commission decides, the Ministry allocates, the regions comply, and the kilowatt appears. A metabolic description refuses to stop at the planning document. It asks: “Who gets to submit a bid, and who is quietly told not to bother? What data about “need” and “shortfall” actually enters the Ministry’s spreadsheet, and what never gets recorded? What software system ranks the tenders, and what weights has some underpaid consultant baked into the algorithm?

When the deadline looms, who cuts corners on installation, and who looks the other way at the inspection stage?”

All of these are questions about protocols, not principles. A protocol might be explicit — an e-procurement platform where bids are automatically ranked according to a published formula. But most protocols are tacit: “We always give at least one contract to the politically connected firm,” or “We slow-walk paperwork for villages that didn’t vote for us,” or “We only approve rooftop solar where the grid is already stable because we don’t want headaches.” These are not written in manifestos, but they are how the machine runs.

From a metabolic point of view, the crucial move is to model these protocols as the real structure of the system, not as accidental deviations from a pure, ideological design. The ideology might say “socialized energy,” the law might say “transparent tendering,” but the metabology says: “Here is the actual pattern of flows that emerges when these rules, incentives, habits, and infrastructures interact.”

It is less like a moral code and more like a wiring diagram.

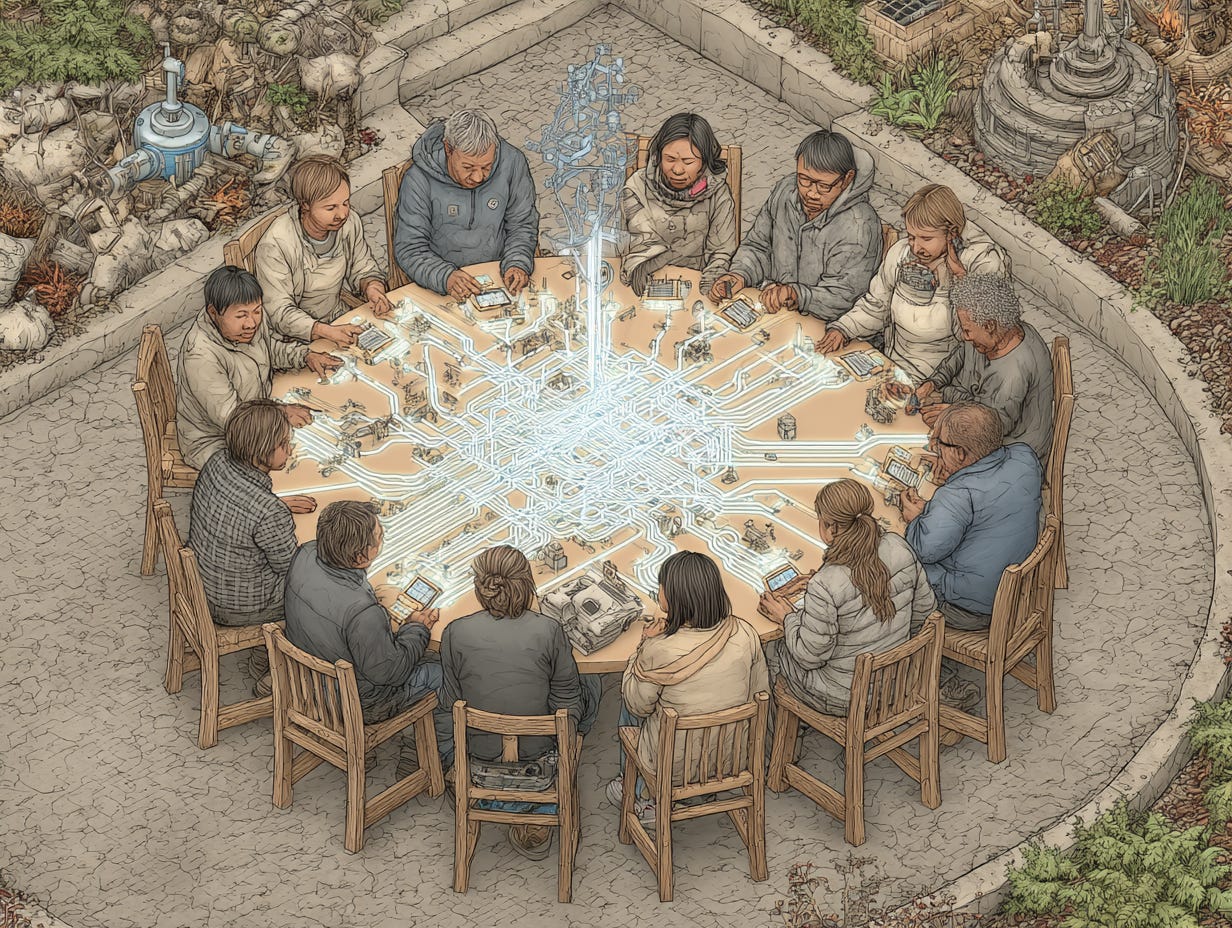

Metabology as Protocol

Once you see that, you can imagine designing metabologies as carefully as we design constitutions or party platforms. You could, for example, build a contracting protocol in which every bid, every need assessment, every delivery milestone is logged in a public ledger; where algorithms are audited; where communities can veto installations that don’t match their needs; where payments are automatically released only upon verified performance. In that world, “provide one kilowatt to every family” isn’t just a slogan; it’s compiled down into stepwise rules that are close to the metal, operating where people, machines, and materials actually meet.

None of this was possible to formalize at large scale before the age of digital infrastructure and big data. We simply did not have the capacity to track flows of energy, money, and information in real time, let alone adjust them through fine-grained rules. Today, we do. That doesn’t mean we automatically have good metabologies; it means we are, for the first time, consciously in the business of writing and rewriting the protocols that run our material life. Metabology is not an abstract model of how the machine should work; it is the set of rules describing how the machine actually runs. It takes into consideration the physical, human, material, and social inputs as they exist in reality.

Even protocols might appear too top-down to some; they might prefer to record existing transactions in a ledger and fit a statistical model on that ledger because metabolic patterns might be too complex for humans to capture in a protocol. We may need AI as an essential intermediary between human metabology and messy life in the real world.

Messy Business

Let me repeat: there’s no need to reduce the complexity of our messy realities. Metabology is very much an account of heterogeneity; it’s not this essence that binds all members of a society in a web of energy and information. Far from it. Instead, consider this quote from Bruno Latour (from ‘Reassembling the Social’):

It claims that there is nothing specific to social order; that there is no social dimension of any sort, no ‘social context’, no distinct domain of reality to which the label ‘social’ or ‘society’ could be attributed; that no ‘social force’ is available to ‘explain’ the residual features other domains cannot account for; that members know very well what they are doing even if they don’t articulate it to the satisfaction of the observers; that actors are never embedded in a social context and so are always much more than ‘mere informants’; that there is thus no meaning in adding some ‘social factors’ to other scientific specialties; that political relevance obtained through a ‘science of society’ is not necessarily desirable; and that ‘society’, far from being the context ‘in which’ everything is framed, should rather be construed as one of the many connecting elements circulating inside tiny conduits.

Now replace ‘social’ by ‘metabolic,’ and run this argument anew. One account of metabology will look for the energetic and informational underpinnings of existing social processes; all those solar panels need paperwork to be completed before they are installed; and all that local paperwork first requires state-level authorities to adopt central policy directives and all those policy directives require the planning commission to approve them, and before you know it, you’re back in ideology. Instead, consider that the paperwork is filed alongside the purchasing of the solar panels - some entrepreneur shook hands with his counterpart in China to buy the panels as soon as the paperwork is completed. Metabolic activity proceeds in parallel; information and material flows proceed in parallel.

Metabology is a science of connection. Its protocols don’t live behind the veil of everyday activity; rather they are executed alongside those activities.

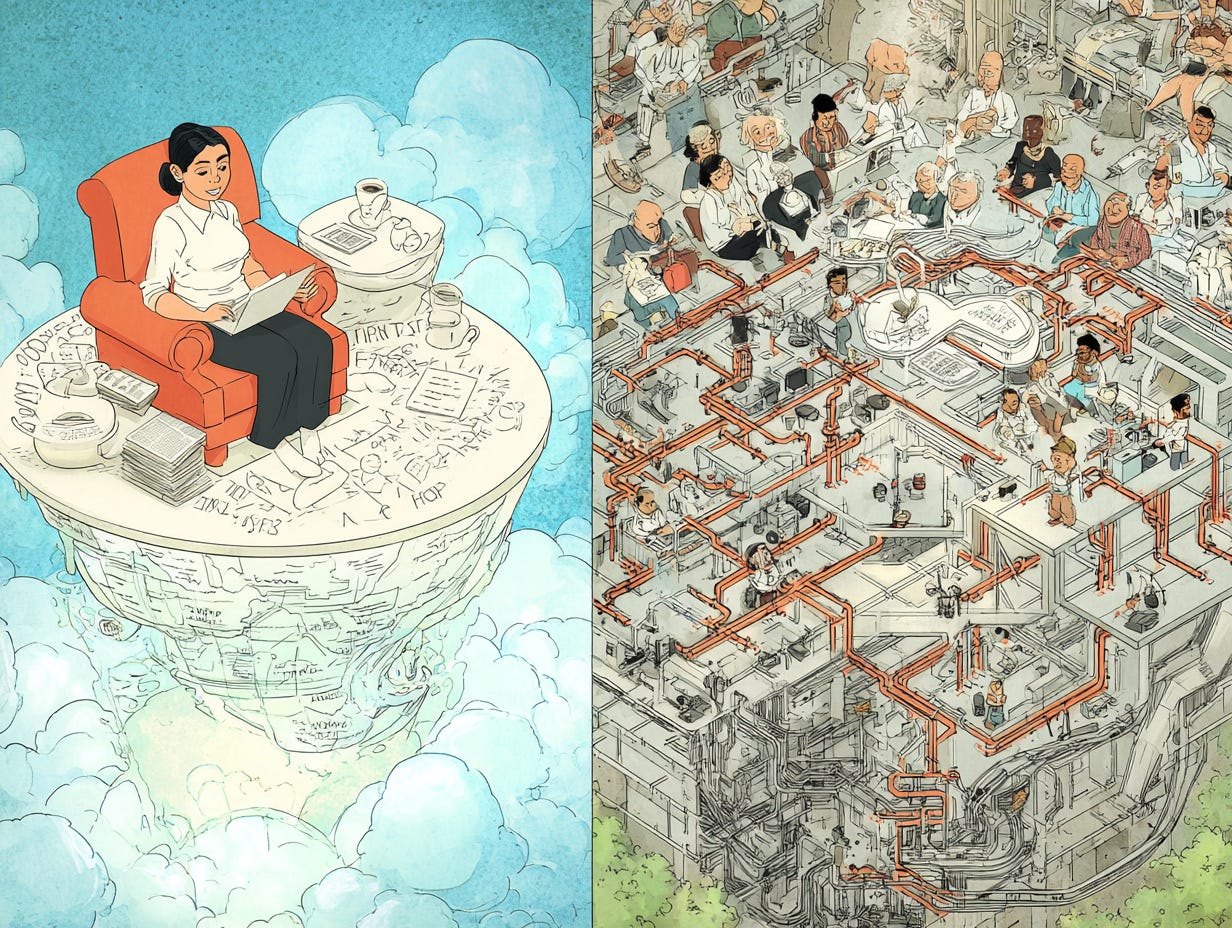

Metabology as Ground vs Metabology as Figure

In gestalt psychology and its offshoots, it’s common to notice that human perception is organized in terms of ‘figure’ and ‘ground.’ During a war scene, when the movie camera pans to the hero’s face, the hero is the figure while battle raging around him is the ground. The figure is what we pay attention to, the entity whose capacity - or lack thereof - to change the world is of interest to us. When the hero is fighting the villain, we want to know who is winning; we don’t care that thousands of other soldiers are being wounded or dying right next to them. The ground, on the other hand, is either inert or, at best, an enabler. The props and the NPCs so to speak. The figure and the ground aren’t fixed. To the writer of a family drama, the argument between the wife and the husband is the figure, and the furniture is a prop. To the set designer, the furniture is the prop and the dialog is someone else’s problem.

In much metabolic analysis - Smil’s “Energy and Civilization” comes to mind - energy and information are enablers, the ground of social structure. That’s not my view: my account of metabology is an account of energy and information as prime movers, as heroes in our social journey. Energy and information don’t create social order behind the scene; no, not at all. They are right there: when an entrepreneur shakes hands with their Chinese supplier for the inputs for a solar farm, the handshake acts as a high-information signal that can then trigger future material flows. Information - the handshake, in case you were wondering - is right there; it’s part of the scene, not behind the scenes. If I were a movie director, I would focus the camera on the hands, not at the flunkies cheering in the background.

This shift in perspective - from prioritizing the ideological “figure” to scrutinizing the metabolic “ground” to refocusing on the metabolic “figure” is the key to grasping and reshaping modern power. Ideologies offer a grand narrative of intention, but metabologies provide the concrete script of execution. By focusing on protocols, data flows, and material transactions, we move past distant principles and into the realm of actionable change.

To build a genuinely new world, we must stop debating manifestos alone and start designing better metabologies - both stacks and protocols - for our shared material reality.

Rain Check

Let me end with a short list of Metabological ideas I have written about in the past and want to flesh out in greater detail in the future plus a couple of ideas for which I have notes but I haven’t written anything.

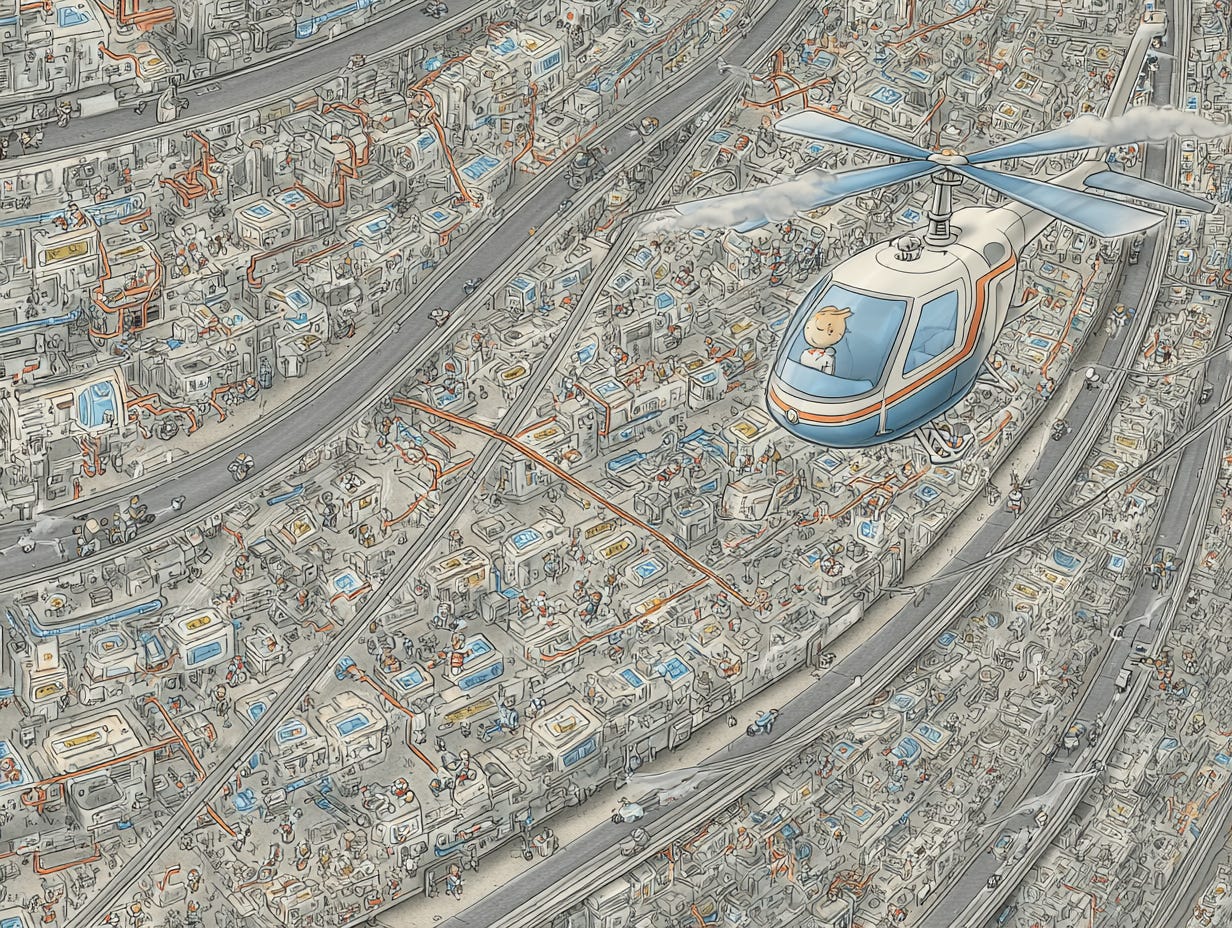

I explored Metabolic Sovereignty, moving beyond the sovereignty of borders to the sovereignty of flows. We will see that power belongs to those who control the conversion points - the semiconductor fabs, the shipping lanes, and the data centers.

I (briefly) examined Metabolic Development, asking how we can expand human capabilities not through infinite GDP growth, but through reorganizing material flows to fit within planetary boundaries.

I am yet to map the US and Chinese Metabolic Stacks, analyzing the geopolitical divergence between the “Prediction Stack” (US/organized around AI and data) and the “Production Stack” (Chinese/organized around energy and matter).

I am yet to explain ‘Mandalarity,’ a new geometry of world order that replaces the ‘poles’ of the Cold War with the overlapping, radiating circles of a networked world.

I am not sure when I will get to these, for I have a completely different topic that I want to explore in 2026.

I hope the end of the year treats you well!