I started the Pauper when I was reading Machiavelli’s “The Prince.” While reading NM, I thought to myself: ‘Machiavelli wrote for rulers; wouldn’t it be nice if someone wrote a version of the Prince for the ruled?’ The Pauper is for those who live under power, not the ones who wield it. The mice scurrying under the dinosaur’s feet. Prince or pauper, we need to see our current world as Machiavelli might have, and reading Herman Kahn is a start. Machiavelli was a man of letters, not numbers, but the modern Machiavellian such as Kahn are comfortable with 1,2,3…

In Contradiction

Marxists often talk about the inherent contradictions of capitalism. For example: every capitalist wants to maximize profits and one way of doing so is to minimize labor costs. But if every capitalist reduces their labor costs, who will buy the output of all those capitalist enterprises?

The same contradiction arises today: suppose every capitalist reduces their labor costs by 50% through automation. What will all those unemployed workers buy? Indeed, it’s not clear what a price signal means when anything and everything can be produced at the press of a button. It’s one thing to say that the labor theory of value is wrong, but can there be any such thing as value if there’s no labor?

While I am not devoting myself to the contradictions inherent in class and property,I find the concept to be useful well beyond its origins. For example, contradictions can manifest at the cosmic scale, if only in speculation.

The Dark Forest

“Xiao Luo, Yang Dong often spoke of you. She said you're in... astronomy?”

“I used to be. I teach college sociology now. At your school, actually, although you had already retired when I got there.”

“Sociology? That’s a pretty big leap.”

“Yeah. Yang Dong always said my mind wasn’t focused.”

“She wasn’t kidding when she said you're smart.”

“Just clever. Nothing like your daughter’s level. I just felt astronomy was an undrillable chunk of iron. Sociology is a plank of wood, and there’s bound to be someplace thin enough to punch through. It’s easier to get by.” .....

“I've got a suggestion. Why don’t you study cosmic sociology?”

“Cosmic sociology?”

“A name chosen at random. Suppose a vast number of civilizations are distributed throughout the universe, on the order of the number of detectable stars. Lots and lots of them. Those civilizations make up the body of a cosmic society. Cosmic sociology is the study of the nature of this supersociety.”

Thus starts Cixin Liu's "Dark Forest," the second book in his "Remembrance of Earth" trilogy, and arguably the most extraordinary work of science fiction in this century.

Existential Politics

Cixin Liu is an interesting man- He's an engineer by training, but instead of fixing the world, he imagines new ones. A cosmic sociologist as he calls one of his characters. And his new worlds aren't always pretty.

Mr. Liu taught me about cosmological caution. Perhaps you have wondered so: “the universe is so big, the more we learn about other solar systems, the more it becomes apparent that almost every single one of them has planets in orbit. Surely some of them host life of some form, and surely some of those go on to develop human like intelligence.” The individual probabilities are all small, but you got to multiply them with the number of stars in the sky and those are huge.

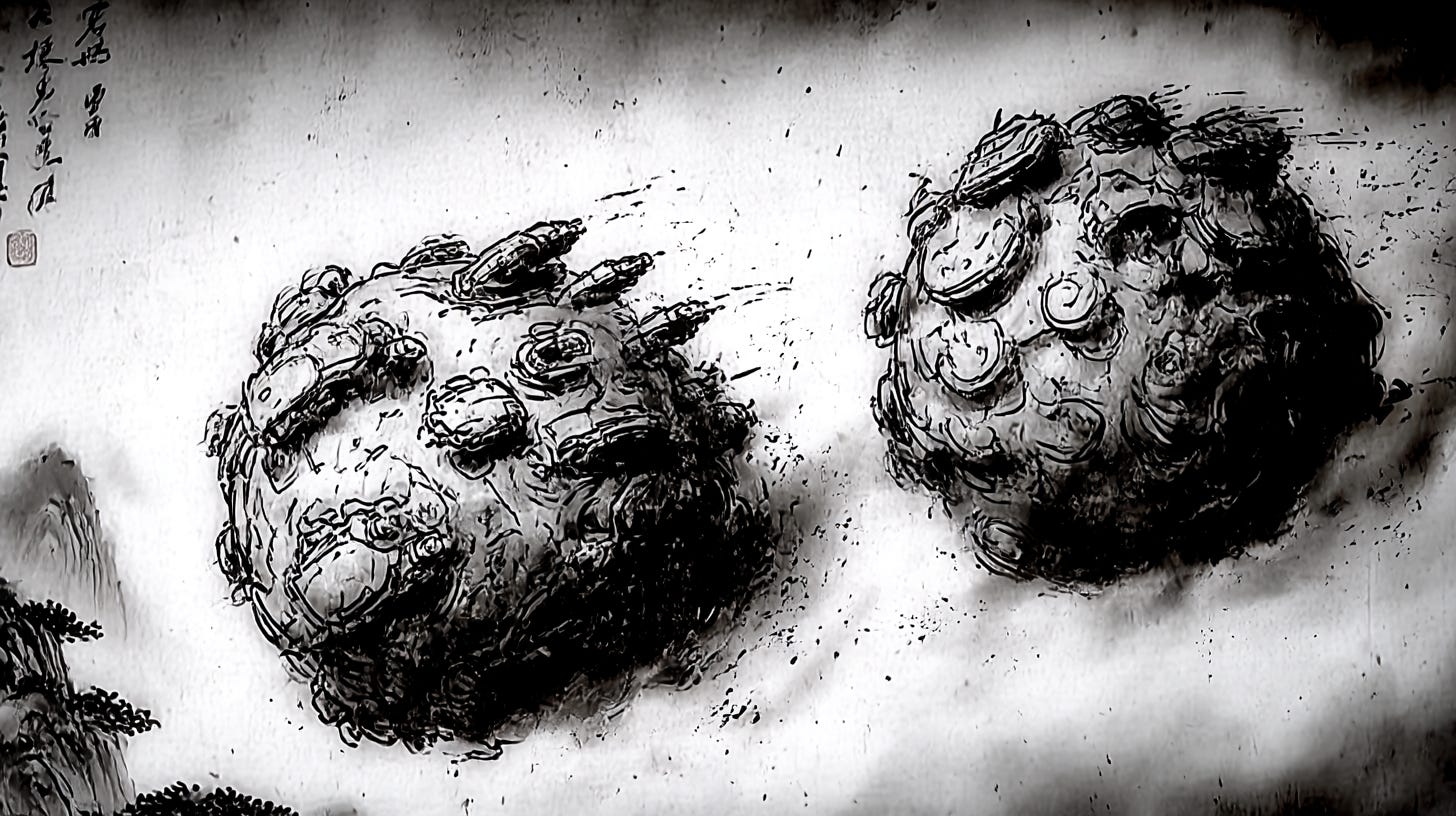

So why haven't we detected any signs of ET? That's the Fermi paradox, named after Enrico Fermi, the great Italian physicist. Mr. Liu has an unorthodox answer to the paradox. It's there in the title of the book - "The Dark Forest." According to Liu, any civilization smart enough to take over a planet-hello humanity! - should immediately go dark and silent, like it was preparing for a cosmic invasion. For why would you expose yourself to much stronger civilizations who would love to use you for lab experiments or afternoon snacks? And in this ruthless cosmos, if you detected an alien intelligence, wouldn't it be better to shoot first and kill them all before they get a chance to do that to you?

Existential politics ain't pretty.

People who claw their way to the top are a distrustful lot for whom malevolence is a survival skill. Aggregate that malevolence at cosmological scale and you get the Dark Forest. We aren't at cosmological scale yet, but dark forest calculations can emerge even at the planetary scale.

In fact, dark forest reasoning is one of the signs of planetarity: it lays bare the contradictions inherent in the Anthropocene.

Planetary Sociology

I wonder why the US didn't use nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union between 1945 and 1949, when the US was the only possessor of the doomsday device. I am here, writing this essay while the sun shines on my face through my office window because Truman had some scruples despite the urgings of some of his generals.

In a gruesome but distinct improvement, the Dark Forest of unilateral bombing got replaced by MAD, i.e., mutually assured destruction, a phrase coined by Donald Brennan, who worked for Herman Kahn at the Hudson Institute. Planetary politics needs a new kind of political thinker, one who can perform mad calculations with ease. One with deep technical knowledge and a bleak view of human nature. Herman Kahn was one such person. John von Neumann and Edward Teller were two others, but Johnny was dead by 1957, and Edward likely didn't understand the newly developing social sciences (like the Game Theory that John v. N. helped create) well enough to be a dark doctor. As a result, Herman Kahn is the only one of the three stooges that concerns us.

All three are considered to be models for Dr. Strangelove in Kubrick's movie of that name, but Herman Kahn more so than the other two. His ideas made him a little crazy in the eyes of others (modeling the end of civilization will do that to your reputation), but just as Machiavelli shocked his contemporaries, we need people who can work out the consequences of Armageddon. The foreword to Kahn's book has Klaus Knorr saying:

In the analysis of military problems since the war, the contribution of civilians has been unprecedentedly large in volume and high in quality.

In the new model of war front-ended by nuclear weapons, and with the Air Force as the most important arm of the military, the soldier, or even the general, is not that important. Tomorrow's wars might need even fewer people with guns: AI will do all the fighting. Instead, you need people who can think in systems (if malevolently) and build institutions and chains of command around mathematical models.

OK, maybe that didn't work out so well, for a man steeped in this new view - Robert McNamara - failed miserably in Vietnam, but there's an element of truth to the claim that the modern Machiavelli has to be able to crunch numbers and analyze models.

A few lines further down in the foreword:

Indeed, On Thermonuclear War is as remarkable for its sophisticated exercises in method as it is for the substantive solutions and proposals it offers. Without his masterly command of method, it would have been impossible for Herman Kahn to examine such an extraordinary range of interrelated problems and, compared with the extant literature, do it so exhaustively.

MAD is a logic of managing nuclear contradictions. It might have been adequate for Cold War nuclear strategy but the Kahnian style of physicsy natural science and rationalist social science is very poorly equipped to tackle the planetary problems of our time. Even the new Cold War between the U.S. and China is unlike the one between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, because the two countries are deeply intertwined. And the rest of the world isn't neatly aligned with one or the other camp. It's a more complex and fluid situation. The new cold war is between competing stacks in a larger network ecology, not between two camps sealed off from one another. This article by Farrell and Newman is a good read on this issue.I will leave you with this quote from that article:

The main problem is that as national security and economic policy merge, governments have to deal with excruciatingly complex phenomena that are not under their control: global supply chains, international financial flows, and emerging technological systems. Nuclear doctrines focused on predicting a single adversary’s responses; today, when geopolitics is shaped in large part by weaponized interdependence, governments must navigate a terrain with many more players, figuring out how to redirect private-sector supply chains in directions that do not hurt themselves while anticipating the responses of a multitude of governmental and nongovernmental actors.

Now for some speculation:

Green Kahn

What would Herman Kahn make of our current planetary predicament? Climate change and ecological collapse present a different challenge from nuclear annihilation—they’re slower, more diffuse, harder to model with the clean mathematics that made MAD so intellectually seductive. But some tools from the Kahnian collective might be useful:

First, the scenarios. Kahn made his reputation by thinking the unthinkable—mapping out nuclear exchanges with the bloodless precision of an actuary calculating car insurance premiums. A planetary Kahn would do the same with tipping points and feedback loops. What happens when the Amazon becomes a net carbon source? When the Greenland ice sheet passes the point of no return? When crop failures cascade through global supply chains?

To think the planet is also to think the end of life on this planet.

Second, the numbers. Kahn loved his decision trees, even when they involved millions of dead people. A green Kahn would insist on quantifying everything: biodiversity loss per degree of warming, economic damage per meter of sea level rise, the probability distributions around methane release from thawing permafrost. The numbers are more uncertain, because we are talking about a system with billions of variables, not just two actors, but the act of modeling forces you to think systematically about interconnections and second-order effects. But of course, this is exactly one of the things that institutions such as the IPCC is doing.

And then comes the uncomfortable part, the trade-offs that made Kahn the model for Dr. Strangelove: what losses are acceptable? How much of Bangladesh can we write off? How many species? At what point does adaptation become surrender? This is where the dark forest logic gets really dark: preparing for the world where cooperation fails and it’s every nation for itself.

Kahnian thinking is inevitable in a Polyconflict world. It needs a new logic of contradiction.